From: Los Angeles Daily News

www.dailynews.com (video posted)

HOLLYWOOD - The Rev. Craig X Rubin read aloud a passage from 1 Kings as the sun set and his congregation prepared for the Sabbath.

Flicking a lighter to the lone candle atop the podium, Rubin burned a bud of marijuana on the flame. He puffed it out, walked to each of the eight members sitting in the pews and waved the smoldering cannabis around them.

This, Rubin proclaims, carries the prayers of Temple 420 to God.

That's the God of Isaac and of Jesus, because members are Christians and Jews. That makes the congregation Rubin founded last summer unique.

But what really sets it apart - and the reason Rubin will be in court Friday - is the temple's use of marijuana as a religious sacrament.

"I am willing to preach the Bible and go to jail if it means getting my message out there," the 41-year-old Panorama City man said. And he knows how strange that sounds.

"I'm a Jewish kid from Beverly Hills who went to UCLA. I could have been a lawyer making $250 an hour like the rest of my friends, or a TV producer. Instead, I'm teaching the Bible, selling weed on Hollywood Boulevard, facing seven years in jail - of course I'm crazy."

The temple's problems actually began as a poisoning investigation performed by homicide detectives. One day last fall, a delivery driver and a security guard were given baked goods from Temple 420, said police spokesman Kevin Maiberger. Both became violently ill and almost died.

No charges came of that, but a few weeks later, on Nov. 3, an undercover officer joined Temple 420. Five days later, at 4:20 p.m., police raided it.

The temple's assets were seized, as were Rubin's. He, his 18-year-old son and another man were charged with one count each of selling or transporting marijuana and one count of possessing marijuana for sale.

"They were trying to set it up under the guise of a religious right and then be able to sidestep marijuana laws," Maiberger said. "The deal was for a $100 initiation fee and $100 annual fee, you could buy all the pot you wanted for quote-unquote `religious purpose.' That's bull----."

Rubin, however, continues to distribute marijuana six days a week to the temple's members - there are more than 400 who have paid the initiation and annual dues - for a "requested donation" of $60 for an eighth of an ounce.

He continues to burn marijuana as a sacrament at Friday night services and preaches on the weekends - Old Testament on Saturdays, New Testament on Sundays, always at 4:20.

His defense relies on his insistence that God wants people to enjoy cannabis - for recreation, religion and industry - and his belief that federal and state laws protect his religious practices.

"It's not a laughable argument," said Eugene Volokh, a UCLA School of Law professor and religious freedom expert. "It's just an uphill argument."

Temple 420 would need to demonstrate that its beliefs are sincere and that marijuana use is not the foundation of the religion but part of a broader ethical system, Volokh said.

Also, the organization would need to prove that its practices don't come at the expense of a compelling government interest.

"But it's not open and shut," Volokh said.

In 1996, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that Rastafarians, who believe marijuana is a sacrament, could use federal law to defend their use of the drug, but not to defend distribution or possession with the intent to distribute.

Last year, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously that a small religious group in New Mexico could use a hallucinogenic drug in its services.

Groups often opposed to each other - from the American Civil Liberties Union to the National Association of Evangelicals - had supported O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal in its defense against the government.

But the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993, cited in the Rasta and O Centro cases, doesn't apply at the state level, and that's where the charges against Rubin will be heard.

California has not passed a law similar to the federal one, and the state Supreme Court has not clearly defined whether the state constitution provides greater religious protection than the First Amendment.

And, of course, there are plenty of Temple 420 skeptics.

"I would inherently be suspect ... of someone attempting to use the Bible as a justification of their desire to smoke marijuana," said Brad Dacus, founder and president of the Pacific Justice Institute, a legal defender of Christian values. "It's not unusual for people to try to use religion as a pretext for purposes of carrying out their pleasures."

Temple 420's tenets stem from Rubin's Jewish childhood, conversion to Christianity and experience taking peyote in American-Indian sweat lodges.

A pro-pot Republican partial to dark suits and red ties, Rubin hangs the American flag behind his podium and gushes about Ronald Reagan. He has been a marijuana activist since his days at UCLA in the early '90s.

A "roper" - who believes hemp is a medicinal marvel and a panacea for fiber, food and fuel shortages - and a "doper," Rubin was dubbed "Hollywood's Wizard of Weed" by High Times magazine and was a consultant on Showtime's hit "Weeds" for two seasons.

While undergoing a family crisis three years ago, Rubin began studying the Bible and, he claims, God revealed to him cannabis' status as the tree of life.

Last year, after the Supreme Court ruled on O Centro, Rubin reasoned he could openly practice his new beliefs, which he describes as "Judeo-Christian" and "Bible based."

In August, Scott Linden, a Pasadena attorney who has helped open several medical-marijuana dispensaries in the San Fernando Valley, filed paperwork with the Secretary of State's Office that registered Temple 420 as a religious corporation.

The organization, however, did not file for tax-exempt status, said Franchise Tax Board spokesman Patrick Hill.

Religious services began Aug. 26, and Craig Roberts, who added the X to his name after studying Malcolm X and changed his last name back to that of his Jewish grandfather, started going by "reverend."

Rubin did not attended a seminary but was ordained in 1990 by the Universal Life Church, an interfaith organization that offers "Free Instant Online Ordination."

"Using sacrament as a way to elevate my spirituality blew me out," said temple member Evan Goding, 29, of Orange, who drives to Hollywood each week with his Jewish girlfriend. "I was like, no way. It just clicked. It made so much sense.

"I've always believed that the world as a whole would be better if most people would just try marijuana. It brings out the better in people. And I'm sorry it's not legal; I'm sorry I can't use it for my religious beliefs without being persecuted."

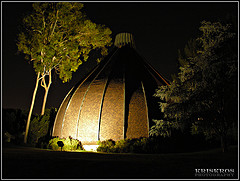

Temple 420 is located in a strip mall at the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea Avenue, next door to an H&R Block and across the street from a Christian Science Church. Fifteen to 30 people stop by most days to pick up pot, said the cashier, who wouldn't give his name.

Rubin gets his stash from the same guys who sell it to medical-marijuana dispensaries, but he charges about 20 percent less per eighth of an ounce. Income goes to pay salaries and support the temple, he said.

He insists he turns away about half the people who try to join; new members must sign an agreement professing, among other things, that "the God of the Bible created cannabis ... for the healing of all nations."

"There are six medical-marijuana clubs within walking distance of here," Rubin said. "If you're a liar, you don't need to come here. Pretend you are sick."

But it is clear some of Temple 420's members aren't interested in the religious services. The sanctuary seats about 40. Some members have never attended.

"For me, it was worth it," David Donahue, 37, of West Hollywood said of joining the temple. "If I didn't get it through him, I would get it through one of my friends' dealers - and I don't know anyone here.

"Two hundred bucks, to some people, it's a lot. It's a lot to me, don't get me wrong. But we pay for convenience."