From: Los Angeles Daily News

www.dailynews.com

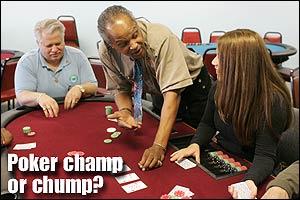

Five card players sit around a Reseda poker table while the dealer takes lessons from a homeless man.

"Make sure you lay the card flat. You gotta lay it flat, otherwise everyone can see," the man tells an aspiring actress who paid $750 for six weeks of dealer training.

The instructor wears unstrapped black overalls, leather sandals and socks, an olive green shirt and a tie-dyed tie. He is Ellix Powers, former crack addict, recovering vagrant and professional poker player - a competitor in the World Series of Poker that starts in Las Vegas today.

From beneath the Ventura Freeway, Powers burst onto the poker stage in 2004, winning two tournaments at the Bicycle Casino in Bell Gardens before becoming one of the most memorable characters at gambling's biggest tournament.

Since then, he's been living in Reseda or Arleta or Long Beach - pretty much anywhere there's a friendly couch - while he waits for his investments to pay off. He's starring in an unfinished independent documentary about the hard life of poker players and teaching at the Poker Academy on Sherman Way.

Powers, 53, is too busy with teaching to spend as much time gambling but he didn't want to miss the World Series. The first of 45 events begins today; the no-limit hold 'em world championship will run from July 28 to Aug. 10.

In the past few years, poker has become a national phenomenon, a roll of the dice that gives more skilled players an edge but offers a rush that some pros describe as better than sex.

At the 2003 World Series, an unknown Nashville, Tenn., accountant - aptly named Chris Moneymaker - won the main event and $2.5 million. Moneymaker beat a field of 839. Last year, the $7.5 million champion had to outlast 5,618.

"The Moneymaker effect has sent a very clear signal that just about anyone can win our tournament," said World Series Commissioner Jeffrey Pollack. "It's pretty unique that the housewife from Peoria can pay to enter and end up sitting at a table with one of the top players in the world."

Moneymaker made a lot of people believe novices had a chance in any poker game, something that couldn't be said about rookies at the Boston Marathon, the Master's or Wimbledon.

So some have shifted from the suit-and-tie life to hustling online poker games and card rooms. But the specter of riches remains an illusion for many more.

"It's no different than playing in the NBA. There are hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of kids who think they are going to make it to the NBA. But there are only 400 players in the NBA," said Pollack, a former National Basketball Association executive. "The odds of making a living competing at the absolute highest level are very, very slim."

Powers knows that.

In 2004, he incited the World Series' second-most memorable moment, his 15 minutes of fame replayed over and over on ESPN reruns.

At the final table for limit hold 'em, Powers did everything he could to disrupt the game's natural flow.

He bet and raised before being dealt cards. He offered patronizing apologies for his capricious play. He thanked opponents for losing while they were still in the hand. He flat out talked trash like former Laker Gary Payton.

"You're disrespecting the game," author James McManus scolded him.

"I can raise in the dark anytime I want," Powers shot back, referring to his move of betting without looking at his cards. "I'm going to do it every time now."

His erratic play got the best of McManus, who quickly called a bet from Powers when all McManus had was queen high. Powers taunted him, albeit inaccurately.

"You called me with a jack high? You called me with a jack high? He called me with a jack high," Powers repeated after goading McManus into the bad play.

"This guy is nuts. I like him. He's good for poker," pro John Hennigan mused. "I'm having fun. I never have fun. This guy is making me have fun."

Powers eventually got bumped in seventh place and strutted to the cashier.

"Do I get any money here? Do I get any money?"

He got $40,040. But Powers has only won about $12,000 at tournaments during the two years since, according to a database of pros at pokerpages.com. He's also won and lost an unspecified amount playing in casinos and mostly online.

"Poker is a big, cruel beast," Powers said in an interview. "There's not a lot of sympathy in the game. There ain't no refunds."

As he sat down for lunch at La Tortilla Loca in Reseda, he asked a reporter who was buying.

"I don't eat that much," he said, adding that he usually doesn't order food and just waits for friends' scraps.

The waitress approached.

"What kind of beer you got?" Powers asked her.

Interrupted and told free beer wasn't part of the deal, he ordered water.

"I was born in the service," Powers said as he began to unfold his history.

His father, Elliott, was an Air Force colonel, and Ellix grew up in a strict house.

"There's nothing I know about him," Elliott Powers, now an attorney in Colorado Springs, Colo., said of his son. "He didn't get a college degree; he's living under a bridge. He's been very disappointing."

The family moved a lot. After graduating from high school in Sacramento, Powers left for college in Kansas, where he met a woman.

She left for Utah, he followed. They had a daughter and parted ways.

Powers ended up in Reno and found cocaine before escaping to Kansas City, Mo. There, he met another woman. After they married and had a daughter, they quickly divorced, and Powers set out for California.

Los Angeles offered another clean slate, but the casinos south of downtown and the crack cocaine flourishing in that area in the early 1990s were too strong a pull.

"I was dabbling with the devil," he said.

Then, one day three years ago, Powers had an epiphany in between panhandling under Highway 101. He had been reading "More Than a Carpenter," a book by Christian author Josh McDowell, and Powers decided he needed to dedicate his life to Jesus Christ.

"I used to always pray, hope God would get me out of this mess," he said. "Eventually, he caught up with me."

Shortly after, in March 2004, Powers won two tournaments at the Bicycle Casino and pocketed $46,535. After the World Series, he returned to L.A. and tried grinding out a living at area card rooms.

A year ago at Hollywood Park he met Stuart Locascio, a Panorama City jeweler with hopes of opening a poker school in the San Fernando Valley.

Locascio believed there was a market for training dealers, servicing parties and providing a place for novices to practice. Poker Academy opened in December with Powers as its poker education director.

The academy opens at 11 a.m. daily and closes when Locascio or Powers decides no more clients are coming, usually after 8 p.m.

His duties haven't left Powers much time to visit casinos. Plus, he needs a lift to get there because his '98 Pontiac Firebird is parked in Reno, Nev., home of the Peppermill Hotel Casino, which Powers considers his permanent residence.

Lacking much time in casinos, Powers hasn't been able to find a financial backer. These venture capitalists, if you will, offer a trade-off: Play for free, but return some, often half, of the winnings. They are the lifeblood of many high rollers.

But Powers said he garnered enough to enter four or five World Series events at the Rio All Suite Hotel and Casino, including $10,000 for the main event. He also plans to hang around the casino and look for suckers throwing money away in nontournament games.

Ed Moulton first met Powers at one of those tables during the World Series last year.

They got to talking, and Powers quickly asked Moulton for $200 so he could enter a satellite tournament, which, if he won, would pay his entry into a bigger event. Moulton agreed.

Powers called the next day. "Oh man, I'm so depressed. Things didn't go my way," Moulton remembered hearing.

Later, though, Moulton ran into a mutual friend who said Powers didn't even enter the tournament.

"This guy was like, `Watch out for Ellix. He's a street hustler,"' he recalled. "That only made me want to hang out with Ellix more. When his stay was up at the Little Hotel, he crashed with me for a few days."

While Powers' life story is unique, his financial struggles are not.

Gamblers are notorious for their "leaks" - extracurriculars that siphon away a chunk of their winnings. Some of poker's biggest stars win hundreds of thousands of dollars in tournaments, and then lose it playing craps or betting on sports.

Without question, poker favors the more skilled, and, many would argue, the more patient. It is a game of information. The more rationally players evaluate their cards against what their opponents might have based on betting patterns, the more they'll win.

Still, poker is gambling and it attracts people who enjoy taking risks, said David G. Schwartz, director of the Center for Gaming Research at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

"Nick the Greek was the biggest gambler in the history of the 20th century," Schwartz said. "He ended up playing dollar games down in L.A., and when he died, they had to take up a collection for his funeral."

Powers' leaks were always drugs. But now he's sober and has a regular job. He doesn't have a place of his own but at least he has friends who do. And he's living with more stability than he's known in 20 years.

Yet like an entertainer remembered as a one-hit wonder, he is desperately looking to move beyond his "jack-high" fame.

"You can have one record or you can do one movie and you can be OK for a while, but until you follow through, you really ain't made it yet. But that's where I'm at, and I'm working on it," he said. "I don't want to own everything. I just want to be in charge of my life."